SO this week I was wondering what I’d do my weekly four-things-I-want-to-share-with-the-world post about, and the answer landed in my inbox. (Actually, it pinged me via Facebook, but inbox sounds better.) A friend—a male friend—sent me something (that has by now no doubt made its way around the world a couple dozen times) and said he thought I’d like to see it. The following day, another friend, also a guy, found me on Gmail chat and sent me a link to a podcast he thought I should write about on this blog. The men in my life seemed to be choosing this moment (well, three out of four of them anyway) to tell me about cool/interesting/weird things they wanted me to know about, so why not take advantage of it? So here’s my first reader-generated blog post.

1. If I were to start in strictly chronological order, this would have to go first. My friend Hasnain emailed me an article more than a month ago and I meant to write about it then (and I have the draft to prove it) but somehow it never got written. (A weekend trip to the Catskills may have gotten in the way.) It came back into my life through this fresh BBC post. From my incomplete draft:

April has not been a good month to be a blogger in India [May wasn’t much better and June is not looking so good either]. On April 11, the Department of Information Technology greatly tightened the rules governing Internet speech laws in the country, adding many broad and vaguely defined instances in which the government could shut down your website. A few days later, the U.S.-based watchdog organization Freedom House released its report on Freedom on the Net in India, and we didn’t do so well. Though India has no substantial political censorship, according to the report, bloggers and online users have been arrested in the past year, and our press freedom status is only “partly free.”

Many of the new “rules” stand out. Amongst the tidbits of personal information that can be collected from you, the Internet user, are “physical, physiological and mental health condition,” and, most bewilderingly, “sexual orientation.” Seriously? It’s not clear whether giving out this information is mandatory or not, but given that it can be handed over to the government for a number of reasons, it’s troubling, at best.

Canadian media artist runran, who took this photograph, says that Internet speeds in Pushkar, India, are akin to paint drying

Even more disturbing is this rule, which prohibits Internet users from displaying or hosting information that “is grossly harmful, harassing, blasphemous, defamatory, obscene, pornographic, paedophilic, libellous, invasive of another’s privacy, hateful, or racially, ethnically objectionable, disparaging, relating or encouraging money laundering or gambling, or otherwise unlawful in any manner whatever; harm[s] minors in any way” or “threatens the unity, integrity, defence, security or sovereignty of India, friendly relations with foreign states, or or public order or causes incitement to the commission of any cognisable offence or prevents investigation of any offence or is insulting any other nation.”

From the BBC post:

The onus on host websites to remove objectionable content is a cause for concern to Mahesh Murthy who runs Pinstorm, a digital marketing agency in Mumbai which manages clients’ online brand presence.

“Any individual can write to us and say that piece of content offends us and without any recourse we have to take it down,” he says.

“This gives us an extremely onerous responsibility to be able to police every bit of content before it goes out,” adds Mr Murthy.

The new guidelines are, in part, a response to the 2008 terrorist attacks in Mumbai, planned with the help of cell phones and anonymous email addresses. And other governments have similarly restrictive rules. But India’s record in using vague laws to go after its political opponents is not reassuring anyone.

2. The Facebook pinger, my friend Zed, sent me this Guardian article with British author V.S. Naipaul’s inflammatory remarks. In an interview with the Royal Geographic Society this week, he claimed that he considers no female writer his match. You’ve no doubt read or heard of this piece, which has been causing so much furor in the UK and here in the United States, already, but here are some choice bits:

In an interview at the Royal Geographic Society on Tuesday about his career, Naipaul, who has been described as the “greatest living writer of English prose”, was asked if he considered any woman writer his literary match. He replied: “I don’t think so.” Of [Jane] Austen he said he “couldn’t possibly share her sentimental ambitions, her sentimental sense of the world”.

And also:

The author, who was born in Trinidad, said this was because of women’s “sentimentality, the narrow view of the world”. “And inevitably for a woman, she is not a complete master of a house, so that comes over in her writing too,” he said.

But the part that spawned a mini-series of follow-ups was his claim to be able to tell work written by a man as opposed to a woman from a short sample:

He said: “I read a piece of writing and within a paragraph or two I know whether it is by a woman or not. I think [it is] unequal to me.”

The Guardian humorously decided to query its readers to find out who among us can claim the same perspicacity as the Nobel Laureate with their “Naipaul test.” (Through sheer guesswork, I scored five out of 10.) The UK’s Telegraph also devised a similar test, though with five samples only. (In that one, I only guessed one correctly, and ironically, I guessed that the excerpt by Naipaul himself had been written by a woman. Wonder what Naipaul would make of that.)

Naipaul has been given enough publicity in the past week, what with his reconciliation—after a period of 15 years—with Paul Theroux over the weekend, and now this. This Wall Street Journal blog had the right idea, when it published an interview with Jennifer Egan, the 2011 winner of the Pulitzer Prize for her novel A Visit from the Goon Squad (which, coincidentally, I just finished reading this past weekend), in which she said:

He may feel like he’s dealt a difficult and painful blow to women, but he makes himself look silly and outdated. And honestly, pretty vain.

Read this 1998 interview Naipaul gave to The New Yorker for an insightful portrait of the author.

UPDATE: I just came across this piece in the Indian newspaper Mint (where I’ve published several travelogues over the years) by Supriya Nair, which impressed me so much that I’m tempted to quote it in full. But that’s bad blogger etiquette, so here are the bits I liked best:

[Y]ou’ve probably seen these charts that came out earlier this year, which ran some numbers on how many women writers were reviewed in America’s top literary magazines — and how many women reviewers wrote for these publications. In some of the Anglophone world’s most liberal, forward-thinking — indeed, downright groundbreaking — publications, the imbalance on these counts isn’t small. In fact, it’s shocking.

Go look at those charts again. I’ll wait.

So, as you can see, women writers have bigger things to worry about other than VS Naipaul not liking their feminine sensibilities. (I mean, what next? Gay writers too caught up in unimportant things like sexuality? Japanese writers write too much about Japan? Derek Walcott just not understanding the West Indies? I’m agog, Naipaul. Agog!)

But — are they really bigger things? When I read Naipaul’s reported statements, after I laughed at him as you laugh at Internet trolls, I couldn’t help but think of the literary establishment responsible for the negligible importance given to women writers and reviewers, as the VIDA numbers demonstrate. VS Naipaul is a Nobel Laureate, read, reviewed and debated extensively — not to mention celebrated — in the pages of global opinion-makers like Harper’s Magazine (number of male reviewers in 2010: 27. Number of female reviewers: 7). And The New York Review of Books (number of male authors reviewed in 2010: 306. Number of female authors reviewed: 59). The New Yorker (male reviewers: 29. Female reviewers: 8).

Go read the full post here.

3. My friend Irfan (sometime Gmail chatter and full-time Canadian resident) sent me a link to this CBC podcast the other day, with this endorsement:

I was just amazed at this woman’s strength, courage, determination and vision.The odds were heavily stacked against her. The environment, very hostile. Her demographic, a woman in a male dominated society.She has a great vision to rebuild her country especially the weakest and most vulnerable…the women and children of Afghanistan.I couldn’t help but admire her guts and her resolve.She is winning in a society where the best of men hv failed.

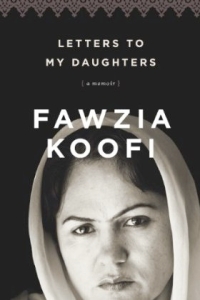

How could I not listen? The interview was conducted on CBC’s The Current, with Anna Maria Tremonti, and the interviewee was Afghanistan’s first female deputy speaker of Parliament, Fawzia Koofi. The segment begins and ends with a letter Koofi reads to her preadolescent girls in case she is killed. At the time she wrote these letters, she was receiving death threats regularly. Happily, she survived to publish a memoir, Letters to My Daughters, and to garner enough support in Afghanistan that she is thinking of running in the presidential elections in her country.

Koofi was the 19th of 23 children, born to the second of her father’s seven wives. In the interview, she says, “My mother didn’t want me to be alive because she wanted me to be a son” so as not to disappoint her husband, Koofi’s father. So they put the newborn out in the sun to die.”I think for a woman, being a woman is a vulnerability sometimes,” she says.

But Koofi survived her first day, and has overcome numerous obstacles since. She was the first in her family to be educated. Her father, who was a Member of Parliament, was killed by mujahideen when she was a toddler. She had to fight with her brothers to be allowed to stand in election. Her stepbrothers would tear down her election posters when they saw them plastered on walls in public. They didn’t want their sister’s face to be displayed in public. “It’s like ownership,” Koofi said. But Koofi was already working by that time, and was financially independent, and so she prevailed. Now, she says proudly, in the last elections where she won a second term, all her brothers stood by her and supported her, putting up the previously reviled posters up in nearby villages to help her campaign efforts.

Now, at age 35, Koofi is a single parent (her husband died in 2003), a Member of Parliament, and a passionate activist for democracy and for human rights and women’s rights in Afghanistan. She is the kind of role model she found in Indira Gandhi, the Prime Minister of India when Koofi was a child.

In an interview she gave to Canadian newspaper The Globe and Mail, she said: “I want to tell to the world, as a woman who has lived through all the situations, that women can make a difference. I want to show how strong Afghan women are.”

4. The final piece of this Four on Friday post comes from my husband, Jatin, who has just begun learning Spanish. Yesterday he came home from his Spanish class with a fascinating bit of information that he knew I would enjoy: in most countries where Spanish is the native language, most women don’t take their husbands names when they marry (I didn’t take my husband’s surname when we married). Not only that, when they have children, the kids’ last names come from both parents’ last names. As About.com explains it, “If Juan López Marcos marries María Covas Callas, their child would end up with a name such as Mario López Covas.”

I’ve always thought that children should have the names of both their parents—and am delighted to know that the Spanish (thanks to an Arabic influence) have been following this democratic custom for decades and maybe even centuries.