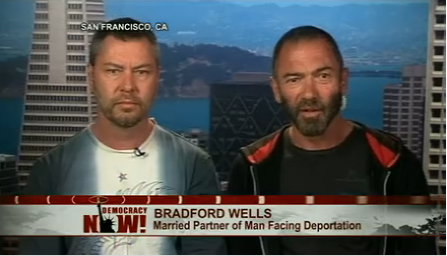

1. AS Jatin and I were driving to the Newark airport this morning to pick up my brother who was coming back from summer vacation in Mumbai, we listened to part of today’s Democracy Now! broadcast. Amy Goodman was interviewing a same-sex, binational couple who are on the verge of being separated thanks to the 1996 Defense of Marriage Act, or DOMA. The act was signed into law by President Clinton and denies same-sex married couples the protections and privileges that heterosexual couples take for granted.

The lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender civil rights organization Human Rights Campaign says that DOMA: “purports to give states the ‘right’ to refuse to recognize same-sex marriages performed in other states.” It also

creates a federal definition of “marriage” and “spouse” for the first time in our country’s history. This is an unprecedented intrusion by the U.S. Congress into an area traditionally left to the states. Marriage is defined as a “legal union between one man and one woman as husband and wife,” and spouse is defined as “a person of the opposite sex who is a husband or a wife.” Marriages that do not fit this description would not be eligible for any benefits offered by the federal government. Under DOMA, even if a state were to recognize same-sex marriages, the federal government would not. The people involved would be unable to receive a number of benefits, including those related to Social Security, survivorship and inheritance.

In the case of the couple interviewed by Amy Goodman, Bradford Wells, a U.S. citizen, and Anthony John Makk, an Australian national, might be separated on August 25—the date that Makk has to leave the country or be subject to deportation. Wells and Makk have been together for 19 years; they have been married for seven. They were among the first same-sex couples to tie the knot when Massachusetts legalized gay marriage in 2004. Makk is also the primary care-giver for his husband, who has HIV/AIDS. Wells described his relationship with Makk:

We got married on July 22nd, 2004. It was really the most momentous day of my life. I had never imagined that I’d be able to get married. And when the opportunity came to me, I realized that I was with the man I had looked for my whole life. I had never felt anything towards someone the way I felt about Anthony. And I didn’t think about us being torn apart in the future. We had been able to keep within the law and get the proper visas. And being together, although it was a lot of work, it was possible. It was only at the end of last year that we ran out of options. Now we find ourselves in this position.

Although last month President Obama said he would not defend DOMA in the courts, it is still on the books. Which means that for the moment, Makk and Wells are facing an uncertain future.

As one-half of a recently married, binational, heterosexual couple, it is especially unfair that Makk and Wells are being denied the immigration benefits that were extended to my husband and me. Makk said:

There’s thousand of couples in our situation. It’s not just us. And something needs to be done. And they can do it. And it’s clear—it’s clearly discrimination. And our relationship, as long as the other thousands of binational, same-sex couples—we have committed relationships, and they are just as committed as heterosexual relationships. And it is very discriminatory, what they are doing. And it’s—and I’m sure that the people will see it, and someone’s going to step in before I either have to leave or stay illegally. And this is something that we have tried over the years so hard not to do.

I remembering going to watch the gay pride march in New York in June, just a few days after New York announced its legalization of same-sex marriage, and the infectious joy in the air. That was a day of celebrations, and for good reason, but now it’s time to roll up our sleeves again. The work of fighting for marriage equality is far from over. Last month Sen. Dianne Feinstein announced a bill to repeal DOMA, called the Respect for Marriage Act. The White House later endorsed it. You can chime in here.

2. The plight of the same-sex California couple got me to thinking about violence: legal violence, physical violence, all the forms that violence can take. It can take the form of indifference, like the indifference of the world to the immense suffering in Somalia, to watch people starve to death and not lift a finger to help. This past week we’ve been hearing about the supposedly “mindless violence” of the rioters in the UK, and the violence of the cuts in government spending and their effects on the poorer classes in that country.

I can’t say I understand what’s going on, or why—and I don’t think I’m the only one—but here are a few pieces that I’ve read recently that have shed some light on these events.

Maria Margaronis blogs for The Nation online about the mood on the streets:

The police are overwhelmed; the politicians nervously continue to plough their furrows. “Sheer criminality,” says Home Secretary Teresa May, as if any attempt to understand what’s at the root of all this rage would imply condoning it. Labour politicians flirt with the temptation to blame government spending cuts, as if such fury could build up in a matter of mere months. Of course the cuts don’t help: they are the final straw, the irrefutable evidence that the poor are now dispensable, outside society. Nor does the larger sense that nobody’s in charge, that the economy’s in freefall, that bankers have been looting the public purse for years, and that our leaders have no idea what to do about any of it. There is a doomsday feeling on the streets of London: time to grab what you can, burn it down and live for now, because who knows what’s coming for us all tomorrow.

Michael McCarthy in the UK’s Independent writes of the death of British civility:

I think people were so frightened because something had been loosed and was on display, which was new to many people – and that was the sight of very large numbers of people, mainly young men, who were no longer constrained by our culture. The role of culture in making British society what it is, and in giving it its remarkable strengths, is not often remarked upon, but it is enormous. We are, or we have been, a culture-bound society: we have been governed largely by informal constraints on our behaviour.

This is in sharp contrast to a society like that of the United States, for example, which is largely a rule-bound society. To give just a single instance: drinking alcohol in the street used to be rare in Britain, because it was frowned upon – but in the US there are local laws specifically forbidding it. The rule-bound society, which is the reason for the vast proliferation of lawyers in the US, arose in America because the founding fathers created a new nation from scratch, starting with a written Constitution that set out the first principles and then writing down and proscribing everything else about people’s behaviour.

Britain, whose governing process evolved slowly and organically, does not even have a written constitution, merely a set of understandings about how things ought to be done.

But these understandings have, in the past, been widespread and very powerful. The bus queue and the idea of queuing generally is an example that persists; I remember my shock and spluttering resentment when I first went skiing, years ago, and stood patiently with the other Brits in the queue for the chairlift and watched as the little French and Italian kids skied to the front and forced their way in.

In the Independent, Camilla Batmanghelidjh responds with the argument that these kids feel no sense of community, of ownership:

If this is a war, the enemy, on the face of it, are the “lawless”, the defenders are the law-abiding. An absence of morality can easily be found in the rioters and looters. How, we ask, could they attack their own community with such disregard? But the young people would reply “easily”, because they feel they don’t actually belong to the community. Community, they would say, has nothing to offer them. Instead, for years they have experienced themselves cut adrift from civil society’s legitimate structures. Society relies on collaborative behaviour; individuals are held accountable because belonging brings personal benefit. Fear or shame of being alienated keeps most of us pro-social.

And in the Guardian, Zoe Williams writes about the psychology of looting, and the lack of worrying about consequences:

By 5pm on Monday, as I was listening to the brave manager of the Lewisham McDonald’s describing, incredulously, how he had just seen the windows stoved in, and he didn’t think they’d be able to open the next day, I wasn’t convinced by nihilism as a reading: how can you cease to believe in law and order, a moral universe, co-operation, the purpose of existence, and yet still believe in sportswear? How can you despise culture but still want the flatscreen TV from the bookies?

And on the BBC, usually my go-to network every morning, anchor Fiona Armstrong interviewed West Indian journalist Darcus Howe in this video that has drawn so much ire that the BBC has had to apologize for it. After Howe said he was not shocked by the events, Armstrong asks: “You say you’re not shocked. Does that mean that you condone what happened in your community last night?” In what universe does a lack of surprise equal endorsement? It goes on in that vein, see for yourself:

Democracy Now! subsequently interviewed Howe along with Richard Seymour, a popular blogger in the UK. Seymour offered his opinion on the riots and the seeming inability of the British authorities to stop the mayhem:

First of all, the circumstances of the killing are that they allowed people to believe that Mark Duggan had a weapon and that he shot that weapon at police officers, and that, therefore, you would conclude they fired back in self-defense. That’s absolutely untrue. The IPCC, the Independent Police Complaints Commission, has confirmed that the bullet that was fired and lodged in a police radio was a police bullet. So, it would be an interesting question, who fired that bullet and why? Which among the officers did so? But it certainly wasn’t Mark Duggan. So, they lied.

But in addition to that, they didn’t inform the family. They let the family find out from the media. And they didn’t send round a family liaison officer to speak to the family. None of the usual procedures, in this highly unusual circumstance, was followed. So, generally speaking, there was a backlash, a reaction against the police, as a result of this.

I just want to say also, in connection with this, Darcus mentioned the competition for the top jobs in the Metropolitan Police. It’s important to note the backdrop here. This is the deep crisis that has shaken the Metropolitan Police in the context of the hacking scandal, in relation to the relationships between top Metropolitan Police officials and the News of the World, News International empire. That has created a deep crisis within the police. It’s an ideological crisis as much as anything else. And so, this is, I expect, one of the reasons for the disarray that they’re in at the moment.

Riots are about power, says Laurie Penny of the Penny Red blog:

Riots are about power, and they are about catharsis. They are not about poor parenting, or youth services being cut, or any of the other snap explanations that media pundits have been trotting out: structural inequalities, as a friend of mine remarked today, are not solved by a few pool tables. People riot because it makes them feel powerful, even if only for a night. People riot because they have spent their whole lives being told that they are good for nothing, and they realise that together they can do anything – literally, anything at all. People to whom respect has never been shown riot because they feel they have little reason to show respect themselves, and it spreads like fire on a warm summer night. And now people have lost their homes, and the country is tearing itself apart.

And Dan Hind has a thoughtful piece on Al Jazeera arguing that the violence is not apolitical, and it is not driven by a single cause:

Civil disturbances never have a single, simple meaning. When the Bastille was being stormed the thieves of Paris doubtless took advantage of the mayhem to rob houses and waylay unlucky revolutionaries. Sometimes the thieves were revolutionaries. Sometimes the revolutionaries were thieves. And it is reckless to start making confident claims about events that are spread across the country and that have many different elements. In Britain over the past few days there have been clashes between the police and young people. Crowds have set buildings, cars and buses on fire. Shops have been looted and passersby have been attacked. Only a fool would announce what it all means.

All these points make sense to me. I don’t have the answers or solutions to this problem, but it seems to me that these authors do a fairly good job of sketching in broad strokes the motives and roots of this maybe not so “mindless” violence.

3. This past week, The New Yorker published a much-discussed anatomy of the violent raid that killed Osama bin Laden in Abbottabad, Pakistan, on May 1. Written by a young freelancer, Nicholas Schmidle, in the narrative nonfiction style, it is a riveting account of what actually happened during that raid, and how the Americans finally “got” bin Laden.

What has been getting press in the aftermath of its publication is the fact that Schmidle did not speak with any of the Navy SEALS who actually conducted the raid; instead, the story was reconstructed from accounts by others who heard the radio communications and who, presumably, were very familiar with the details of the raids. Nowhere in his story does Schmidle reveal that he never spoke with the SEALS; and he tells the tale so skillfully that it seems as though he did. The Washington Post‘s Paul Farhi revealed in this post just how Schmidle got his story. Farhi wrote:

Schmidle says he wasn’t able to interview any of the 23 Navy SEALs involved in the mission itself. Instead, he said, he relied on the accounts of others who had debriefed the men.

But a casual reader of the article wouldn’t know that; neither the article nor an editor’s note describes the sourcing for parts of the story. Schmidle, in fact, piles up so many details about some of the men, such as their thoughts at various times, that the article leaves a strong impression that he spoke with them directly.

Some readers were critical of this. Columbia Journalism Review questioned the secrecy of The New Yorker‘s fact-checking. Women’s Wear Daily collected the criticisms in this column. And the redoutable Poynter devoted many, many words to this minor controversy. (For the record, I think Schmidle and his editors could have made his sourcing clearer without losing the urgency of the narrative.)

But the most piercing critique was made by this Reuters blog, aptly titled, “When There Are No People in Pakistan.” It’s been making the rounds among South Asians on Facebook and Twitter, but I don’t see media critics at CJR or Poynter taking note of it. Presumably only Pakistanis care when their voices are left out of a story that takes place in Pakistan—this is violence by omission, perhaps?

Forgive me, Reuters, for quoting in such depth, but it needs to be underlined and highlighted:

In a post over the weekend which prompted me to re-examine the New Yorker story, Jakob Steiner at RugPundits complained about Orientalism. That in turn led me to look at how small a role Pakistanis play in the story. Pause here, and consider that Pakistan is a country of some 180 million people of diverse religious, social, linguistic and cultural backgrounds. People who fret about their children’s education and grieve for their parents like the rest of us. People who in the office will bitch around the water cooler, and over dinner talk about the weather. And yes. I simplify people’s lives, because those of us who live them (signpost irony here) know how simple they are.

Then start perhaps, by noticing the dog has a name and a breed. He (she?) is called Cairo and is a Belgian Malinois.

Now scroll down to what seems to be the first clear reference to Pakistani civilians. It was in the context of whether President Barack Obama should consider an air strike on bin Laden’s Abbottabad compound or a helicopter raid.

“He (Defense Secretary Robert Gates) and General James Cartwright, the vice-chairman of the Joint Chiefs, favored an airstrike by B-2 Spirit bombers. That option would avoid the risk of having American boots on the ground in Pakistan. But the Air Force then calculated that a payload of thirty-two smart bombs, each weighing two thousand pounds, would be required to penetrate thirty feet below ground, insuring that any bunkers would collapse. ‘That much ordnance going off would be the equivalent of an earthquake,’ Cartwright told me. The prospect of flattening a Pakistani city made Obama pause.”

The helicopter raid decided, the assault plan was fine-tuned. “The SEALs and the dog could assist more aggressively, if needed. Then, if bin Laden was proving difficult to find, Cairo could be sent into the house to search for false walls or hidden doors.”

And of the people who lived in Abbottabad? What of their reaction? Linguistically, they are described in three letters – a “mob”.

”After describing the operation, the briefers fielded questions: What if a mob surrounded the compound? Were the SEALs prepared to shoot civilians?” wrote Schmidle.

The first person to comment publicly on the raid did so on Twitter, a resident who asked what a helicopter was doing in Abbottabad so late at night. He is a man with a full name, a profile and an online identity, who I and thousands of others found and followed easily enough on the day bin Laden was killed. In the New Yorker article, he becomes merely “one local”.

In the final paragraphs of the piece, the journalist writes:

I don’t know what really happened that night from May 1 into May 2. I don’t know, and none of us know, how its repercussions will play out in Pakistan over the months and years ahead. But I would guess that any version of U.S. policy, based on the same thinking behind the New Yorker’s story, that there are no real people on the ground, is unlikely to succeed.

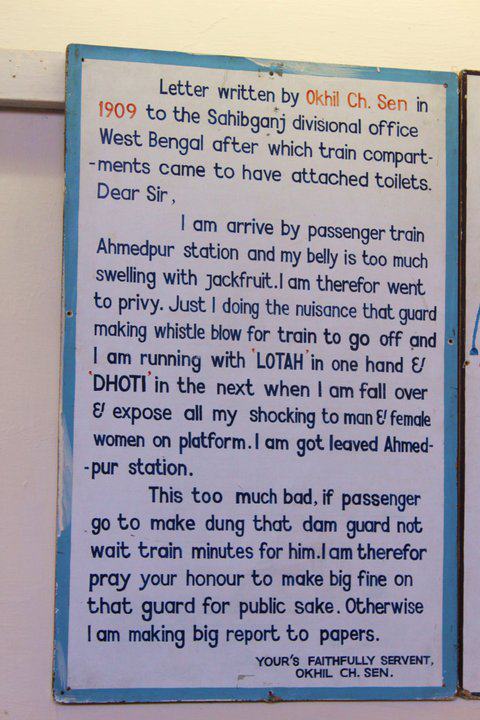

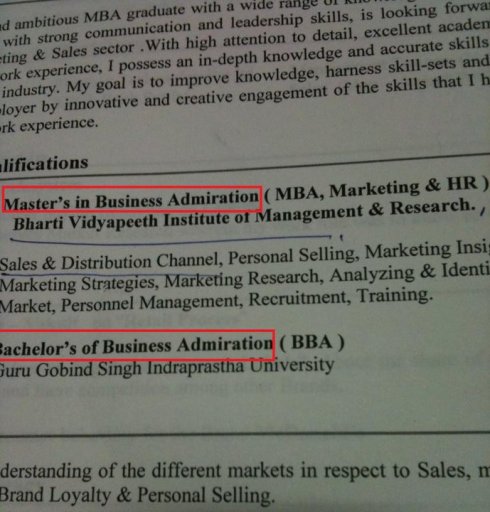

4. To end this piece on a slightly lighter note, I want to mention a mild form of violence to language, but humorously. I recently discovered this Facebook group, English Whirled Wide, which seems to collect images from around the world of quirky, ungrammatical, and just plain funny signage. In case they require a Facebook log-in to view their collection, I am pasting some of their images here:

To celebrate how we can contort and twist and refashion the English language, here’s Zigzackly’s declaration of the 2011 Great Grandson of Godawful Poetry Fortnight, which runs from August 19th to the 31st. To all those who point out that this “fortnight” only lasts 13 days, Zigzackly says, “Poetic license!”

In the spirit of English-mangling and good fun, here’s my contribution:

A journo once went to the sea

Where whales danced and exclaimed with some glee

But the writer took note

And dreamed up a big boat

Thus Moby Dick was created by he!

(Before anyone sues me for libel or defamation, let it be said that this is just my offering to the godawful poetry gods and has no bearing on the actual authorship of Moby Dick!)

In case my feeble attempt has disgusted my dear readers, I will leave you with some real poetry, by the United States’ new Poet Laureate, Philip Levine.

What Work Is

By Philip Levine

We stand in the rain in a long line

waiting at Ford Highland Park. For work.

You know what work is–if you’re

old enough to read this you know what

work is, although you may not do it.

Forget you. This is about waiting,

shifting from one foot to another.

Feeling the light rain falling like mist

into your hair, blurring your vision

until you think you see your own brother

ahead of you, maybe ten places.

You rub your glasses with your fingers,

and of course it’s someone else’s brother,

narrower across the shoulders than

yours but with the same sad slouch, the grin

that does not hide the stubbornness,

the sad refusal to give in to

rain, to the hours wasted waiting,

to the knowledge that somewhere ahead

a man is waiting who will say, “No,

we’re not hiring today,” for any

reason he wants. You love your brother,

now suddenly you can hardly stand

the love flooding you for your brother,

who’s not beside you or behind or

ahead because he’s home trying to

sleep off a miserable night shift

at Cadillac so he can get up

before noon to study his German.

Works eight hours a night so he can sing

Wagner, the opera you hate most,

the worst music ever invented.

How long has it been since you told him

you loved him, held his wide shoulders,

opened your eyes wide and said those words,

and maybe kissed his cheek? You’ve never

done something so simple, so obvious,

not because you’re too young or too dumb,

not because you’re jealous or even mean

or incapable of crying in

the presence of another man, no,

just because you don’t know what work is.

Leave a comment